Cost-competitiveness key to align supply chains towards India: Ind-Ra

June 15, 2020: India Ratings and Research (Ind-Ra) believes that the Covid-19 pandemic will stoke a global policy narrative around the realignment of cross-border supply chains – particularly for the pivotal role played by the Chinese economy.

June 15, 2020: India Ratings and Research (Ind-Ra) believes that the Covid-19 pandemic will stoke a global policy narrative around the realignment of cross-border supply chains, particularly for the pivotal role played by the Chinese economy. However, this realignment will take time to gain momentum.

The ability of other emerging markets, including India, to benefit from a shift away from China will be driven by two factors, first, the ability of these markets to provide cost-competitive alternatives and second, the evolution of the trade policy in various importing nations.

Immediate shift unlikely

Ind-Ra believes that in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic, as economies and businesses operate in a ‘restart and rebuild’ mode, business continuity and near-term sustenance are likely to be the key considerations. Thus, businesses are likely to scout for reliable and tried-and-tested vendors, markets and trade intermediaries.

Additionally, given its position as one of the first countries to recover from the pandemic and its central role in various global supply chains, China and Chinese businesses are well-positioned as reliable, competitive and proven trade counterparties. The agency has already discussed at length China’s crucial role in the global supply chains for various sectors.

Impact of protectionism & indigenisation

Since FY15, the global trade has focused more on indigenisation and even import-substitution. As a result, post the global financial crisis, the share of global exports in the world GDP has started declining. This was most pronounced in FY19 and FY20, attributable largely to the large-scale US-China trade tensions, changes to the Generalised System of Preferences and several other trade policy changes.

Low productivity & India’s competitive position

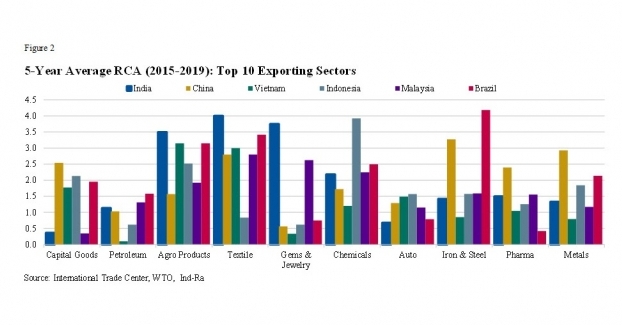

Post the global financial crisis, the share of exports in India’s GDP has contracted significantly – while the gap between the share of global exports to global GDP and Indian exports to Indian GDP has widened further. This, at least in part, has been driven by low factor productivity coupled with a rise in the trade competitiveness of countries such as Vietnam, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia and Brazil – evidenced in India’s lower revealed comparative advantage (RCA) than other exporters. An RCA below 1x indicates the absence of significant competitive advantage.

Consequently, in the absence of deep structural reforms leading to a significant rise in factor productivity and cost efficiencies, India’s ability to increase its share in global exports could prove to be challenging. It is only with a rise in productivity and realisation of economies scale through both forward and backward integration can Indian corporates gain market share globally.

A significant portion of this gap in return on capital employed is explained by the differential rate of labour productivity in China and India between 1990 and 2019, although the labour productivity growth rate has recently been largely similar. In Purchasing Power Parity terms, labour productivity per employed person in China increased over 11x between 1990 and 2019 to $34,863 from $3,055, while India’s labour productivity increased by 4.26x to $20,367 from $4,775 in the same period. This differential further strengthens the need to enhance labour productivity over the near to medium term to present a viable alternative to China in the global supply chain. Ind-Ra believes that for India to achieve an average real GDP growth rate of 8 percent, labour productivity has to grow by over 21 percent in the near to medium term.

De-stressing balance sheets

Ind-Ra has classified sectors in three buckets: (1) highly competitive sectors with strong balance sheets; (2) highly competitive sectors with highly leveraged balance sheets and (3) sectors with weak competitive strength and weak balance sheets. In the first bucket, capital deepening, innovation and economies of scale are likely to facilitate growth in the global market share. These sectors are already well-positioned to leverage their strengths and gain further market share.

In the second bucket, in case of balance sheets are not repaired, the existing competitive strengths could soon be impaired. Players have sound business models, however, deleveraging their balance sheets will be critical. Most players are small and medium enterprises and therefore fundamentally their ability to withstand economic shocks is fairly constrained. As a result, post the pandemic, these sectors could take a while to repair their balance sheets. In the meanwhile, they may forego global market shares.

In the third bucket, deep restructuring of both the balance sheet and business models will be necessary. It will be imperative to enhance productivity while also ensuring a reduction in debt levels to revive innovation, bring about cost-effectiveness and subsequently gain market share globally.